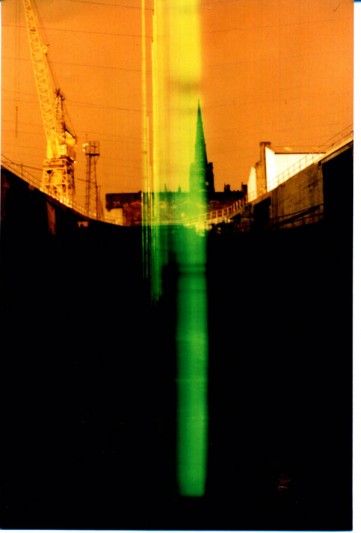

Sojourn. Cammell Laird, Birkenhead 2001

This project involved three stages of development within Cammell Laird shipyard that began with Sojourn (2001) followed by Inland Waters (2002) , The Whitworth, Manchester and ending with Shipbuilding – Past and Present (2004) Imperial War Museum, Salford. All three attempted to give voice to the social demographics of the working environment of this world-famous shipyard, Cammell Laird, through the creative use of shipwrights’ everyday materials and processes. I felt a strong resonance with this site having grown up a short distance from the Clyde shipyards, where many iconic ships were built. Jimmy Reid described the ships built on the River Clyde as some of the most ‘magnificent artefacts that Britain had every created… which eclipsed all in tonnage and fame.’ Mine was the first artist’s residency in the 176-years of the shipyard’s history. This was an Arts Council ‘Year of the Artist’ funded award

Peter Dunn, the shipyard Director gave the following report on the impact of the artist residency scheme in the shipyard as a: “valuable and invigorating insight. A worthwhile educational experience for all…Workers at all levels and from all age groups showed an interest in Patricia ‘s work and many contributed in a tangible way to the exhibits. The proof of this interest is the large number who came to visit the end of project exhibition in their own time and with their families. This must surely be regarded as a high commendation for the artist and her work from those it was meant to influence” Peter Dunn (Silver 2001).

Background

Sojourn (2000) was a major milestone in the development of my work as an artist and clarified my thinking about the magnitude and the limitations of making site-specific interventions within working communities. Cammell Laird shipyard was an unknown landscape and its concealed world resonated with my experience as a child growing up around the Govan shipyards in the 1960’s and 1970’s. The dry docks, cranes, large steel structures and metal forms could be glimpsed from the top of a double-decker bus. Hundreds of Dockers would block the main road as they changed shifts leaving the gates of Fairfield’s shipyards in Govan.

Gaining access to Cammell Laird as artist in residence was both exciting and overwhelming. It was a shipyard of epic proportions covering approximately 200 acres comprising a wet basin, seven dry docks, a construction hall big enough to build sections of ships and presented issues relating to scale, grandeur and accessibility.

The Cammell Laird shipyard in Birkenhead had been a major source of employment and had built 1,350 boats and ships. These were world famous ships, which included the first steel ship, the Ma Robert, built for Dr David Livingstone in 1858 and launched into the River Mersey from the Cammell Laird slipways. It was estimated that the shipyard had employed more than 350,000 men over the years. During the period 1950-1973 Cammell Laird, as with other significant shipbuilders in the UK,

had gone from being world leaders in the shipbuilding market to a much smaller specialist industry. There are several speculations about this decline, one being that British shipyards failed to modernise and increase productivity when compared to competing yards in Japan, West Germany and Sweden (Connors 1987). Another hindrance to the development of shipyards was the fractious relationship between trade unionism and management which did not exist with competitors in Japan who followed a consensus management style and West Germany’s Mitbestimmung union system. (Lorenz 1991) A deep-seated resistance to change was rife in shipyards with demarcation and restricted practices bringing production to a standstill. ‘high wage costs and a strong pound (as opposed to low wage costs and an undervalued Yen) further compounded attempts by shipyards to run profitably” (Chida and Davies 1990). Cammell Laird closed down in 1993 as a shipbuilding yard after running up huge losses in the 1980s in the face of competition from Far Eastern competitors and re-opened as a ship repair company in 1997. It is well documented that a major contributory factor in the decline of the shipbuilding industry was due to the lack of investment by shipyard owners during the post-war boom years and again in the 1960s.

In 2000 at the start of my residency the company had started work on the Costa Classica liner and in particular on the giant mid-section which was to be inserted in the middle of the ship designed to lengthen the liner by 45m. Unfortunately, the Costa Classica mid-section project was never completed. At 3 pm on the afternoon of November 23, 2001, the captain of the Costa Classica was in the Bay of Biscay, heading for Merseyside when he received an order out of the blue to head back to Genoa. The shipping company, Costa Crociere, after inspection, decided that the mid-section was not ready to be inserted. I had observed the mid-section in the shipyard alongside the world’s media, workforce and managers at the test launch just days before this happened. I watched the mid-section sway over to the side and listened to the distressed voices onboard communicating to managers on walkie-talkies informing them that water was flooding into the vessel. The mid-section was quickly hauled back to shore. I discovered later that the managers had agreed with Costa Crociere that no money would change hands unless they delivered on time and within budget. This was a first-time venture for the shipyard with the ambition to move out of ship repair and back to shipbuilding. The loss of the Italian business left Cammell Laird in a precarious financial situation. It was a blow from which it never recovered. I was in the yard in 2001 when the news arrived about the termination of the contract followed by redundancy notices and the closure of the yard.

People and Place

During the residency, I installed seven site-specific temporary artworks. The managing of time was significant to the success of this project: as I was making, installing and experimenting with work in dry-dock areas before they were filled with gallons of water in preparation for the arrival of a ship scheduled for repair.

Before I started the residency, I had approached one of the shipyard directors, Peter Dunn. I showed him my publications, which he threw back across the desk at me, saying he didn’t understand this kind of work. He asked me to send him an outline of what I wanted to do so that he could put this to his co-directors. Nevertheless, my proposal was eventually accepted and the residency began a few months later.

Working in a non-art environment is in part about changing mindsets. It involves developing the ability to convince non-art people about the validity of the artwork. It is using educational techniques and persuasive tactics that are not taught in art colleges. It is a skill that I have developed autonomously through a process of engagement and learning what works.

I decided to form a steering group at the start of the residency; probably one of the most valuable initiatives as it offered me support throughout the residency, especially when the yard hit a crisis point. It was evident that I was also embracing an organisational structure that the shipyard directors could relate to and respect. I invited arts officers, gallery curators, shipyard union and health and safety representatives, site managers and shipyard directors as steering group members.

I was a guest within a strongly patriarchal environment which became evident early on during the health and safety induction where I was presented with a white overall – worn by senior management – to keep me visible and safe whilst walking around the yard. I managed to persuade the manager to swap this for a blue overall. I was concerned that wearing a white overall would alienate me from the 5000 workforce who wore predominately blue overalls. A few weeks after this meeting I was presented with my own bespoke blue overall – – tapered waist and hood with ‘Patricia, Cammell Laird resident artist ‘embroidered with white thread.

Over time I built up a knowledge which helped to inform my work that referred to the channels and methods of communication between the workforce hierarchy. This included the different forms of spoken, written and visual language that is used between management, skilled trades and office staff. The signs used within this matrix of communication is described by Voloshinov as being ’conditioned above all by the social organisation of the participants involved and also by the immediate conditions of their interaction’

I discovered that the shipyards had a power dynamic: a visible hierarchy – coloured overalls were used for different positions and trades: white for manager/ director, red for foreman, grey for engineer and blue for the general workforce. The directors’ rationale for the colour coding – ‘it’s for safety reasons” i.e. if there is a problem in the yard you can quickly identify the right worker for the job by the colour of their overalls. For the workforce, on the other hand, I was told: “It’s great – you can see a white overall from a mile off and run.”

Unlike previous projects, where I had explored empty, silent spaces, the Birkenhead shipyard was full of people, busy and noisy with a permanent workforce of 5,000, although, during the course of the residency about 14,000 engineers, shipwrights and tradesmen came and went as specific tasks were completed. Throughout the year-long process of observing, conceiving ideas, formulating responses, experimenting with materials (and initially failing because of various technical problems), talking to workers and, finally, producing and showing outcomes – at all times I was in full public view of the community.

I was given a porta-cabin studio in the centre of the shipyard, between the dry or graving docks. This is where I would position and gather all the material I collected. My door was open and the men would drop off bits of tools or machinery from around the yard.

Most of the yard’s interiors were full of fascinating traces of Victorian equipment and architecture. My intention during this time was to gain an understanding of the geography of the shipyard, to observe the ways in which the general workforce functioned and to learn about their working environment. It was this growing appreciation of the daily practice of Cammell Laird and the interactions between workers that formed the basis of the artwork which expressed ideas of scale, language and time. I wanted to make artwork that made sense of the vastness of steel constructions and processes juxtaposed with the intimate presence and contribution of the shipwright. To elucidate ‘the space of intimacy and the world space- a blend which is described by Bachelard as ‘intimate immensity’’

I wandered about the shipyard for the first three months – asking questions, making notes, collecting information about specific materials and processes and making connections with the general workforce. I believed that I earned their respect by being around all the time and working the same shifts day and night – dispelling the idea of an artist as an prima donna. The shipyard at night is grim – especially during the winter – every space is open to the elements; every cold metal is covered in oil. All the areas are exposed to a northerly, gale force wind. There are only a few cosy spots. I often had my tea break in the small radio shed where the shipwrights communicated with ships coming into dock and noted the weather report. The men became used to me dropping into their tea areas and observing and asking them questions. The men began to introduce me to others saying. ‘have you met our artist?’

The work commission for The Whitworth exhibition: Inland Waters (2002) was a remake of some of the installations created in the shipyard, including Phosphorescent Levels and Cycle, as well as a collection of finds from around the shipyard. Alistair Smith, Director of the Whitworth in his introduction to the publication described the work installed in the exhibition as a response to the closure of the shipyard as an investment ‘with a sense of a past, and with memory’s power to evoke regret.”

Shipbuilding – Past and Present (2004) was a new work commissioned for a joint exhibition with the work of the late Stanley Spencer by The Imperial War Museum, Manchester. The new work commissioned by the Imperial War Museum, Manchester meant a return visit to the shipyard. The shipyard was then under new management with a reduced workforce from 5000 to three hundred. My research took on the investigation and mapping out of feelings of loss within this industry and I produced two films in response to this sense of loss and at the physically desolate shipyard.